- Categories

- Landscapes

- Zoom in on Artwork

- Print Page

- Email Page to Friend

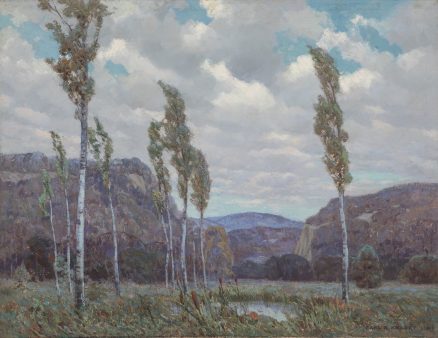

Their foliage tossed sideways in a strong breeze, slender poplars are scattered across the foreground of a broad vista in Carl Krafft’s Ozark Zephyrs. The trees’ white bark sets off the purple tones of distant bluffs and hills, against which they form a thin screen under a sky filled with scudding clouds. Krafft’s loose brushwork complements the evocation of aerial movement even as the forms of the landscape appear timeless. The scene bears no trace of human activity or imprint on nature, yet it is carefully arranged for viewing according to conventions of landscape painting. The distant perspective at the composition’s center is framed by the heights massed on either side, and a foreground pool reflects the sky.

This large canvas was painted to command attention in an exhibition. Described as a “song of the breeze,” by an admiring reviewer in 1915, Ozark Zephyrs was one of two landscapes that Krafft showed in that year’s “Chicago and Vicinity” annual exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago.i Together, they won the fifty-dollar annual prize given by the Englewood Woman’s Club, a South Side group. The following year, both paintings were reproduced in an article on the up-and-coming artist in the Fine Arts Journal, in which Krafft, the “painter poet of the Ozarks,” was praised for serving his country by raising public awareness of the beauty of its landscape through his art.ii Krafft had been painting the region since 1912, but the Englewood Woman’s Prize marked a turning point in his career. By 1916 he was able to abandon the commercial work with which he had been supporting his family and begin painting full time.

According to a plate on the frame, the Englewood Woman’s Club used this painting to honor Myrtle Dean Clark, its president in 1916–1917. The club was one of many Chicago-area women’s and civic organizations that, beginning in the late 1890s, were vital patrons of Chicago artists: they not only funded important prizes but had inaugurated the “Chicago and Vicinity” exhibition, in 1897. Ozark Zephyrs and its companion work, the now-unlocated Dreamland, garnered the Englewood Woman’s Club prize in 1915. Yet the paintings were not added to the club’s own collection: according to the organization’s yearbook for 1917–1918, they were among its “Gifts of Pictures to Schools.” In addition to supporting artists through prizes, Chicago’s women’s organizations such as the Englewood Woman’s Club were active at the turn of the twentieth century in bringing art into public schools. Works such as Ozark Zephyrs, with its poetic vision of unspoiled pastoral nature, fulfilled a Progressive Era conviction in the power of beauty to uplift and civilize city-bound youth and particularly to inculcate wholesome American values in the children of Chicago’s many impoverished immigrants.

Wendy Greenhouse, PhD

i Untitled clipping, Christian Science Monitor, March 5, 1915, in AIC Scrapbooks v. 9, p. 149.

ii Lena M. McCauley, “A Painter Poet of the Ozarks,” Fine Arts Journal 34 (Oct. 1916): 465-472.