- Categories

- Landscapes

- Zoom in on Artwork

- Print Page

- Email Page to Friend

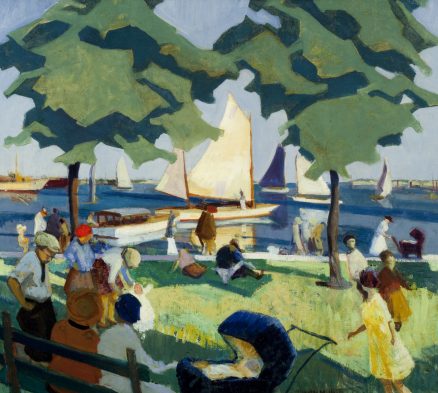

Charles E. Mullin’s painting depicts adults and children enjoying a sunny summer afternoon in parkland bordering glassy water on which pleasure boats float. The flat horizon is framed by two trees, their stylized foliage a mass of angular light- and dark-green shapes. People stroll along an embankment at the water’s edge, relax on a bench at the lower left, or occupy the sun-dappled lawn. The figures’ simple dress and informal postures suggest ordinary folks taking an afternoon’s respite from the pressures of city life; meanwhile, beyond their reach are the distant boats, playthings of the well-to-do. Women with children and babies dominate the scene, but at the composition’s center a man seated on the grass with a newspaper spread across his lap hints at the enforced idleness of the unemployed.

Like many fellow Chicago painters of the 1920s and 1930s, Mullin in this painting refers only obliquely to contemporary social realities, emphasizing instead purely compositional elements. The figures are simplified and generalized; those whose faces are not turned away from the viewer or obscured by hats are almost featureless. Like the exactly placed trees, the figures are arranged to balance colors and forms and they are linked to one another to frame the scene on either side. At the lower right, for example, the handle of a baby pram leads the eye toward the outstretched right arm of a girl in a yellow dress, who in turn looks away toward the lake where another, more distant baby-carriage is propelled by a woman in white.

The exact site pictured by Mullin is unidentified and the painting’s original title is unrecorded. Chicago has several sheltered lagoons along its lakefront where boats are moored seasonally, but hints of a sandy shore on the distant opposite bank may indicate dunes along the Lake Michigan shoreline in Indiana or Michigan. In the late 1920s and early 1930s Mullin exhibited several paintings with titles that indicate shoreline settings; this work may picture a vacation spot of the kind developed to attract city- and suburb-dwellers. Chicago’s progressive painters of the early twentieth century found the social variety of these places as compelling as their natural attractions. Mullin’s painting recalls such works as Anthony Angarola’s Bench Lizards (1922; Bernard Friedman Collection), which he likely saw when it was on display in the Art Institute of Chicago’s annual American art exhibition of 1922. Mullin may have also intended to evoke a more famous precedent, French painter Georges Seurat’s Sunday Afternoon on La Grande Jatte—1884 (1884–1886; Art Institute of Chicago). Seurat’s masterpiece drew considerable attention when it was given to the Art Institute in 1926, not long before Mullin is thought to have painted Untitled (By the Lake), his own image of a waterside park.

Wendy Greenhouse, PhD