- Categories

- Still lifes

- Women artists

- Zoom in on Artwork

- Print Page

- Email Page to Friend

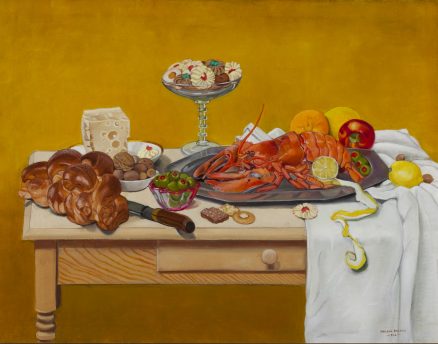

A bright red lobster, lemons, cookies, olives, nuts, cheese, fruit, and a loaf of bread are arranged casually atop a simple table of unpainted wood in Macena Barton’s still-life painting. With their contrasting colors and surface textures, these delectable foods evoke a variety of tastes and tactile sensations and hint at the pleasures of the feast. Critic Clarence J. Bulliet, a champion of artistic modernism and of Barton in particular, praised her “luscious table piece of lobster, bread and all the trimmings . . . It combines the sense of design of the Little Dutch Masters and the gorgeous colors of a Renoir. It errs a bit as art, perhaps, in the direction of forcing the gastric juices to accumulate in the stomach of the onlookers.”i Barton also won the approval of conservative critics for her skills in naturalistic rendering, as demonstrated here in the reflective surface of the silver platter that holds the lobster, the transparency of the footed glass bowl bearing the cookies, and the projecting knife handle balanced over the table’s edge, among other details. The Chicago Tribune’s Eleanor Jewett, for example, enthused over the “mouth watering [sic] arrangement of foods . . . built up around the pleasing personality of a pink lobster” in a painting that “strikes a high [note] for still life in any show of recent seasons.”ii The Lobster was one of a group of some dozen large still-life paintings in Barton’s solo exhibition at the Chicago Galleries Association in 1947. In 1951 she included the work in her show at the Chicago Public Library, and at an unknown date she chose it as the subject of her annual holiday card, where it was captioned Still Life with Lobster.

In noting the hint of the “Little Dutch Masters” in Barton’s composition, Bulliet was undoubtedly thinking of such seventeenth-century painters of tabletop still lifes as Pieter Claesz, whose Still Life Barton likely saw at the Art Institute of Chicago after the museum purchased it in 1935. Her Lobster also closely mirrors Still Life with a Lobster by another Dutch master, Willem Claeszoon Heda; donated to the National Gallery in London in 1947, it might have been familiar to Barton from a reproduction. Yet Barton painted her own still life, with its heightened color and intense realism, in a modern spirit. Supporting the assorted objects is a common American table of inexpensive pine (featured in other Barton still-life paintings), and the pimento-stuffed olives and bakery spritz cookies, if not the lobster, might have been found in the artist’s own kitchen in Chicago’s Tree Studios building. The bread on the left corner of the tabletop is also a striking departure from precedent, for it is a loaf of challah, a braided bread made for the Jewish celebration of the Sabbath and holidays. In an earlier still life called Loaves (1937; Illinois State Museum), Barton painted a challah loaf almost hidden behind other breads, on the same tabletop featured in The Lobster. Here, in contrast, it is a central element, its knobby surface strangely echoing the undulating contours of the lobster, a shellfish forbidden by Jewish dietary law. With such subtly provocative juxtapositions, Barton offers a tongue-in-cheek paraphrase of still-life tradition.

Wendy Greenhouse, PhD

Donated by M. Christine Schwartz to the Krannert Art Museum, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, Champaign, Illinois, in 2023

i C. J. Bulliet, “Still Lifes That Live,” Arts Magazine 21 (Apr. 15, 1947): 9.

ii Eleanor Jewett, “Macena Barton Strikes a High in Still Life Art,” Chicago Tribune, Mar. 23, 1947.