- Categories

- Still lifes

- Women artists

- Zoom in on Artwork

- Print Page

- Email Page to Friend

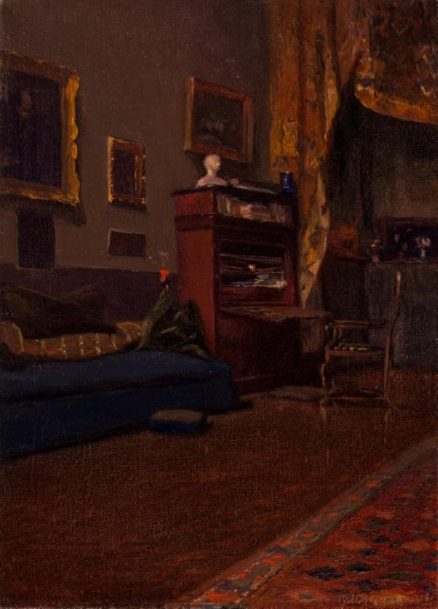

Minerva Chapman’s untitled interior view takes in a corner of the artist’s studio, where a tall drop-front desk, with an armchair pulled up to it, is placed between an upholstered sofa and a hanging golden curtain pulled back to reveal a well-furnished corner of the room. Framed paintings are hung in a random arrangement on the wall; a bust sculpture of white marble or plaster sits atop the desk cabinet; and in the shadowy back corner is what appears to be a case displaying some of the miniature portraits for which Chapman gained a reputation in the first decade of the twentieth century. The deep diagonal recession of space is emphasized by the generous expanse of polished wood floor partly covered by an oriental rug. Bright but diffused light flooding the space from the upper left implies the presence of a high, slanted window or skylight of the kind favored for artists’ studios.

Chapman spent much of her career in Paris. Returning there in 1903 after several years’ hiatus in the United States, she settled into a studio at 9 rue Falguière, in the popular artists’ quarter of Montparnasse. During an earlier period in Paris, Chapman had made several small images of corners of her studio, showing casual arrangements of props, easels, and paintings stacked against the wall to evoke the artist at work. This later studio scene, in contrast, suggests Chapman’s professional success. From her desk, at which the artist is shown seated in a photograph made around the same time as the painting (see Chapman’s biography), she would have managed paperwork relating to her many professional activities. The framed paintings and the display of miniatures seen here stand for an existing body of finished work in diverse formats. The draped curtain and pillow-strewn sofa present the studio not merely as a site of artistic labors but as a material statement of culture and tasteful refinement, a setting to be frequented and admired by prospective clients, according to the practice of many late-nineteenth-century European and American artists.

Chapman’s studio views, with their quiet arrangements of inanimate objects, testify to the importance of still-life painting in her practice, which also extended to landscapes, figure studies, and portraits. In addition to full-size easel paintings and miniatures, she painted numerous small study-like works in oils, made quickly and on site. This technique was highly popular among American artists working in Paris around the turn of the twentieth century, particularly for landscape views. Chapman additionally used it for still-life compositions and studio scenes. Although Interior is painted on a somewhat larger canvas, it retains the sketch-like freshness and aura of unedited immediacy for which her smaller studies were prized. As she often did with such works, Chapman inscribed her name and the date of the painting by incising the wet oil paint with a sharp stylus or the tip of a brush handle.

Wendy Greenhouse, PhD