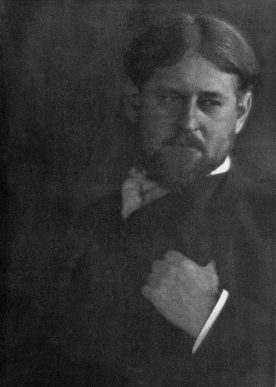

Charles Francis Browne, from a photograph reproduced in The Sketch Book 5 (Jan. 1906).

Charles Francis Browne 1859–1920

Born in Natick, Massachusetts, Charles Francis Browne rejected the mercantile career his father had planned for him. As a youth, he worked in a firm of lithographic printers, beginning his art studies in night classes at the school of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts in 1882. Three years later, he enrolled in the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts to work under realist painter Thomas Eakins. He then went to Paris to study with renowned figural painter Jean-Léon Gérôme. Notwithstanding his immersion in academic figural technique, Browne, inspired by sojourns in the French countryside, began painting landscapes in both oils and watercolors. Returning to the U.S. in 1891, he taught briefly at Beloit College in Wisconsin before settling in Chicago. He painted murals for the Children’s Building at the World’s Columbian Exposition and became an instructor at the Art Institute of Chicago’s rapidly growing school. Along with sculptor Hermon Atkins MacNeil, Browne visited the Southwest in 1894, a trip that yielded subjects for American Indian portraits and figural scenes.

In Chicago, Browne quickly established himself as a spokesman on art matters. In 1897 he founded the journal Brush and Pencil, of which he served as editor until 1900. He was active in the Municipal Art League, the Artists’ Guild, the Society of Western Artists, the Chicago Society of Artists (of which he served as president), and numerous other local and national arts organizations. Browne was also an influential figure as an exhibition juror, teacher, lecturer, and writer on art. A member of such exclusive artists’ coteries as the Little Room, a gathering in the Fine Arts Building studio of Ralph Clarkson, and Eagle’s Nest, a seasonal art colony in Oregon, Illinois, he was closely associated with the local artistic elite. He married a sister of influential sculptor and Eagle’s Nest founder Lorado Taft, with whom he worked in the mid-1890s in the Central Art Association, a Chicago-based organization for promoting art in the American hinterland.

In 1894, Browne’s cautious views on the emerging style of impressionism were voiced by the “Conservative Painter” in the Central Art Association’s influential pamphlet Impressions on Impressionism, whose publication heralded the gradual acceptance of the new mode among American artists and their public. Favoring quiet, intimate scenes and smooth surfaces, Browne adhered to more traditional painting values in his own landscape work. After the turn of the century and with a series of working sojourns in France, however, he became somewhat more receptive to impressionism’s loose, lively brushwork, attention to atmosphere, and high-keyed color. Solidly representational, his paintings, many depicting French and midwestern locales, exemplify the genteel aestheticism of conservative American landscape painting of the early twentieth century and the impulse to express the poetic “feeling” inherent in the local setting.

Wendy Greenhouse, PhD