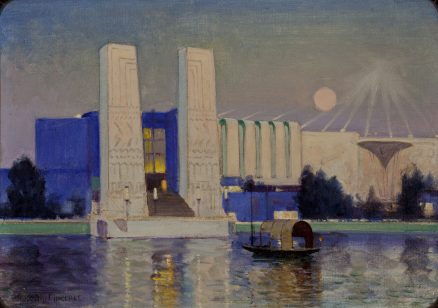

Untitled (Electrical Building at Twilight)

, circa 1934Oil on canvas board, 10 by 14 inches

- Zoom in on Artwork

- Print Page

- Email Page to Friend

Painted at Chicago’s 1933–1934 Century of Progress exposition, this work pictures the Electrical Building from across the South Lagoon, part of a body of water that separated an artificial island created for the fair (today’s Northerly Island) from the city’s shoreline along Lake Michigan. In Peyraud’s image, a covered gondola approaches the landing known as the Water Gate, with its twin 100-plus-foot pylons dedicated to light and to sound. On the right the moon, rising in the pastel-tinted eastern sky, glows through beacons projected from the building’s roof. With its harmonious palette of limpid blues and lavender and its distant perspective, the twilight scene is serene, even elegiac. It evokes a timeless world far removed from the reality of the fair, with its bustling crowds and displays of the latest technology. Even the gondola seems deserted as it glides across the lagoon’s rippling but reflective surface.

Throughout its buildings and grounds, the Century of Progress exposition showcased advances in lighting technology in extravagant applications of artificial illumination, notably on the exterior of the so-called Electrical Group. The striated wall flanking the Water Gate was a curved array of “cascades” of gaseous tubing that created a virtual waterfall of light at night; the nearby Morning Glory fountain contained underwater floodlights that slowly changed color under jets of water for a brilliant evening show; and the rooftop’s seventeen movable searchlights projected twenty-one million candlepower of light into the darkened sky, comprising the largest set of incandescent beams ever assembled.

In his painting, Ingerle conspicuously muted these engineered effects, however, and the twilight setting and distant perspective further transform the scene into a fantasy inspired by mythology and remote pasts. This was not entirely the artist’s interpretation, for even the Electrical Group had its retrospective elements. In form and scale the Water Gate echoed ancient Assyrian, Egyptian, and Greek monumental architecture, while Aztec design inspired Lee Lawrie’s decorative relief sculptures on the pylons. Visitors approaching the Water Gate in gondolas could imagine themselves in faraway Venice. Moreover, by the time Ingerle painted this work, during the fair’s 1934 season, the strong color of the Electrical Group recorded by Frederic M. Grant in The Fountain, Electrical Building had been subdued under a coat of white paint, furthering the association with the marble temples and palaces of idealized antiquity. Ingerle’s romantic take on the Electrical Building was also consistent with the current direction of his painting: by the late 1920s, when he had come to strongly identify with tradition and conservatism both politically and artistically, he was painting rural American landscapes and their inhabitants as subjects uncontaminated by modernity.

Ingerle was one of a group of artists, known as Groh Associates, commissioned to make paintings of the Century of Progress fair with a focus on its unprecedented architectural use of color and light. His group of small painted sketches, all on lightweight, portable canvas board and likely made on site, also included a depiction of the Morning Glory Fountain seen at a closer range.

Wendy Greenhouse, PhD

Donated by M. Christine Schwartz to the Newberry Library, Chicago, Illinois, in 2023